Humans: The IoT device of tomorrow

Elon Musk is what many people likely call a visionary. After all, this is a man who wants to colonize Mars and let people commute to work via capsule. You'd be forgiven if you thought Musk just sat around coming up with ideas on his own way to work—which he did. That was The Boring Company, which is a proposed tunnel building, infrastructure company. (No, there's no plan for the tunnels. As of yet.)

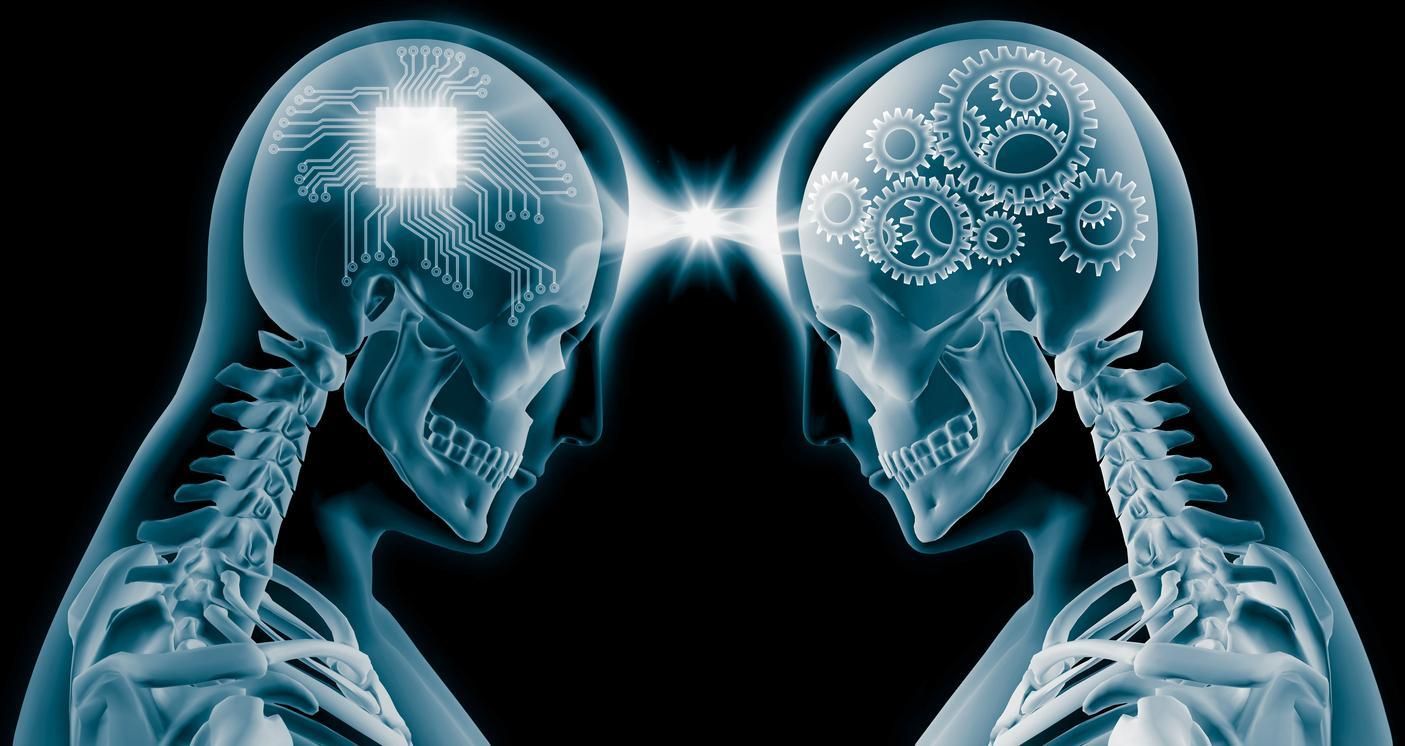

Musk's latest idea however is the one that pushes into territory more foreign than another planet or deep into the Earth's crust: our brain. His concept, Neuralink, is looking at implanting devices into human brains, allowing them to link up to information and software. In essence you become the gadget as well as the interface, merging with artificial intelligence. This kind of human-machine interface could be the next terrain in connected technology, turning you into an IoT device.

Already chipped

One writer has called Neuralink's concept the ability to give users a "wizard hat." But Merlin hat or not, the idea of having hardware embedded in the body is one that tends to cause a wince-like reaction. This is a very skewed reading we've done at GearBrain: completely non-scientific, with a randomly selected group of participants. But try it yourself. Talking about putting a chip or some kind of device that links to another in someone's body provokes mentions of dystopian movies. "Terminator." "Total Recall." "Divergent." It's not a pretty picture.

Yet we chip our dog and our cat. We track our kids via mobile app. Why not chip ourselves for faster service at Starbucks? BuzzFeed reporter Charlie Warzel did just that in 2016, implanting a RFID chip in his hand as a device to buy food. And—it worked. He paid for lunch at a small restaurant in Manhattan's Lower East Side, with his hand. Well, the chip in his hand that was then linked to Venmo. But his hand completed the sale.

His story generated quite a few comments including one reader who wondered how easily you could hack someone's financial accounts just by shaking their hand. Another reader said he was willing to have implants to make his life better, but chips to speed up financial transactions? Not his thing.

And that's a line many do draw: Pacemakers? Cochlear implants for hearing? An implanted insulin pump? Microprocessors—or chips—are hard at work in these. But as that one commenter noted: one person's hearing aid is hardly the same as a chip in our fingertip paying for our cappuccino, or another uploading Kung Fu into our brain. Or transmitting our location. Or taking away our control. Chips put into our bodies to cure an ailment are one decision. Chips put into our bodies to augment ourselves in a way we don't yet need—quite another.

Working chips

Of course in many ways, we already chip ourselves on a daily basis, and willingly. There are nearly five billion unique mobile subscribers worldwide, according to GSMA Intelligence, GSMA's research arm, which represents global mobile companies and groups. That's nearly 70 percent of the world's population, which today is just under 7.4 billion people, according to the U.S. Census Bureau's World Population Clock.

Each unique mobile subscriber is someone with a device that links through a signal to an end point: a mobile tower for phone service, the internet, the web. That's a chipped connection, one that can track your location, and even what you're looking at online. While it's not embedded in your forearm, or in your frontal cortex, that chip is practically embedded in your hand. Ever see the reaction people have when you ask to take their mobile device at a movie screening? Or a dinner party? Exactly.

We can, however, choose to put down our chipped device. We can also turn it off. And that uplinked gadget is not tethered physically to our bodies. The power to step away remains ours. Not so at one startup incubator in Sweden called Epicenter, where some workers are choosing to be injected with rice-sized chips that open doors, buy afternoon snacks and even operate devices, reports the Associated Press. There, being chipped isn't exactly policy. But 150 employees, from about 100 companies headquartered there, opted to get injected with the implant as of April 2017.

Even that—a chip implanted into the human hand—is not the same as a device proposed by Musk that would be connected to the brain, and then meant to interact directly with artificial intelligence. What would push us to agree to this kind of body-machine connection?

Neuralink's web site is sparse in terms of details. The best description is one that comes up via Google when searching for the company: "Neuralink develops high bandwidth and safe brain-machine interfaces." The key word to read here is "safe." The key question is: Will humans will ever feel safe about connected hardware in their brain? That future may seem unwritten. But to some, like Musk, it's only a matter of time.